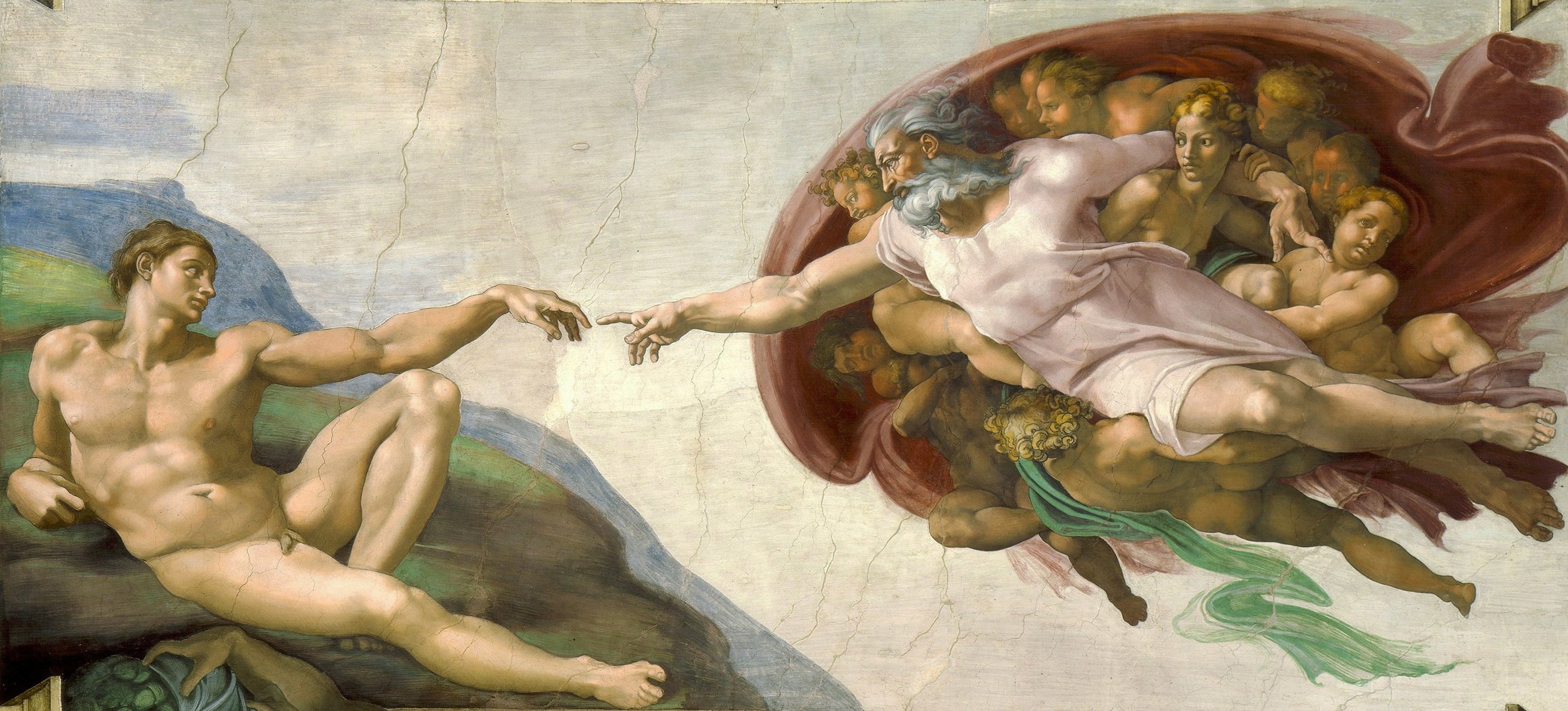

IN THE BEGINNING:

Metaphysics, then and now.

Metaphysics frustrates simple definitions. While the word ostensibly suggests a subject matter “beyond physics,” this etymology proves false. Actually, the name derives from the Greek “Ta meta ta phūsika”—a title applied to the fourteen books of Aristotle’s lectures on “first causes” (and a phrase not used by Aristotle himself). Aristotle referred to the philosophical subject matter of metaphysics by four names: first philosophy, first science, wisdom, and theology. Broadly, it concerned things that do not change.

While this definition sufficed for many centuries, it unraveled in the seventeenth century. At that time, philosophers foisted questions onto metaphysics that had classically belonged to physics: the mind-body problem, free will, and personal identity across time, among others. Synchronously, the British physician Gideon Harvey coined the term ‘ontology’ to denote metaphysics’ original transcendental philosophical territory. A debate quickly (re)emerged between realists (who believe that universals exist) and nominalists (who, broadly, do not), which raised further questions concerning the nature of substance.

Today, metaphysics attempts to answer questions concerning the difference between necessary and contingent truths; space and time; mental and physical; persistence and constitution; and causation, determinism, and freedom. To query these quandaries, philosophers have developed several analytical systems. Some draw on philosophical logic, some on canonical quantification theory, others on purely verbal reasoning. The vast array and complexity of metaphysical problems has led some to deny the possibility of metaphysics.

We believe that the subject matter of metaphysics, in both its classical and modern iterations, merits rigorous academic research. Moreover, we hold that it repays personal study. Finally, while we acknowledge that recent approaches to the philosophical discussion concerning—for example—free will and the mind-body problem merit exploration in their own right, these should not be explored to the neglect of classical wisdom.